CASE REPORT

published: 24 May 2022

doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.893830

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience | www.frontiersin.org 1 May 2022 | Volume 16 | Article 893830

Edited by:

Siegfried Othmer,

EEG Info, United States

Reviewed by:

James H. Lake,

Western Sydney University, Australia

Meike Wiedemann,

Owner of Neurofeedback

Clinic, Germany

Fabian Bazzana,

University of Turin, Italy

*Correspondence:

Regula Spreyermann

Specialty section:

This article was submitted to

Brain Health and Clinical

Neuroscience,

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

Received: 10 March 2022

Accepted: 15 April 2022

Published: 24 May 2022

Citation:

Spreyermann R (2022) Case Report:

Infra-Low-Frequency Neurofeedback

for PTSD: A Therapist’s Perspective.

Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16:893830.

doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.893830

Case Report: Infra-Low-Frequency

Neurofeedback for PTSD: A

Therapist’s Perspective

Regula Spreyermann

*

Praxis Dr. med. Regula Spreyermann, Basel, Switzerland

The practical use of a combination of trauma psychotherapy and neurofeedback

[infra-low-frequency (ILF) neurofeedback and alpha-theta training] is described for the

treatment of patients diagnosed with complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD).

The indication for this combined treatment is the persistence of symptoms of a

hyper-aroused state, anxiety, and sleep disorders even with adequate trauma-focused

psychotherapy and supportive medication, according to the Guidelines of the German

Society of Psycho-Traumatology (DeGPT). Another indication for a supplementary

treatment with neurofeedback is the persistence of dissociative symptoms. Last but not

least, the neurofeedback treatment after a trauma-focused psychotherapy session helps

to calm the trauma-related reactions and to process the memories. The process of the

combined therapy is described and illustrated using two representative case reports.

Overall, a rather satisfying result of this outpatient treatment program can be seen in the

qualitative appraisal of 7 years of practical application.

Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), neurofeedback for PTSD, neurofeedback combined with

psychotherapy, hyperarousal, trauma, C-PTSD

SETTING FOR THE TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH COMPLEX

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER USING

TRAUMA-FOCUSED PSYCHOTHERAPY AND NEUROFEEDBACK

For indications such as complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD), a close interdisciplinary

collaboration is called for. In this case, a close collaboration between the psychiatric doctor’s

office with a focus on psycho-traumatology (Peter Streb, MD, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy,

Basel, Switzerland) and the office for psychosomatic medicine offers neurofeedback (Regula

Spreyermann, MD Internal Medicine, Basel, Switzerland).

In trauma-focused psychotherapy, Peter Streb works according to the Guidelines of the

DeGPT, the German Society of Psychotraumatology (https://www.awmf.org) with stabilization,

trauma confrontation, and processing including specific interventions such as Eye Movement

Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) or Imagery Rescripting and Reprocessing

Therapy (IRRT).

The additional psychosomatic treatment includes psychoeducation, neurofeedback,

mindfulness training, imaginative therapy, and general support throughout the process and

with optimization of the conditions of living (

Lake, 2015).

Once a week, the effects of th e combined therapy, the condition of the patients, acute problems,

medication changes, and the overall process are discussed interdisciplinary between the doctor’s

offices. Based on this regular exchange, decisions are made with respect to changes in training

Spreyermann Neurofeedback and Psychotherapy for C-PTSD

protocol or shifting the focus to either more psychotherapy or

more neurofeedback or only on one of them. This happens either

because the objective has been reached or because it became clear

that the additional effect is insufficient.

INDICATIONS TO ADD NEUROFEEDBACK

TO TRAUMA-FOCUSED

PSYCHOTHERAPY IN THE TREATMENT

OF PATIENTS SUFFERING FROM C-PTSD

Patients are sent to an additional treatment with neurofeedback

when, despite intensive trauma-specific psychotherapy and

different medications, insufficient relief from the typical PTSD

symptoms has been achieved (

van der Kolk et al., 2016). In these

cases, infra-low-frequency (ILF) neurofeedback (Othmer, 2017),

followed by alpha-theta training (Othmer and Othmer, 2017), is

used as an additional treatment of choice (Lanius et al., 2015).

There are also cases where a trauma-induced chronic

dissociation hinders effective psycho-therapeutic trauma therapy,

as emotions cannot be perceived by the patient (Lanius and

Frewen, 2015). In these cases, neurofeedback ca n help to lead to

better self-awareness, greater mental stability, and improved self-

regulation, which then in turn makes it possible to work on the

trauma (

Gerge, 2020a).

PTSD SYMPTOMS AND WHAT MAKES IT

C-PTSD

The typical symptoms of PTSD are symptoms of chronic stress

induced by trauma. These symptoms include hyperarousal,

sleep disorders, panic attacks, nightmares, flashbacks, muscle

tension, fatigue, lack of concentration, emotional instability, and

depressive symptoms. One speaks of C-PTSD if the persistent

PTSD symptomatology has led additionally to personality

changes and emotional dysregulation according to the criteria

of the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision

(World Health Organization, 2022), which are typically induced

by persistent traumatization during childhood (emotional or

sexual abuse or violence or neglect) or during adulthood

following torture, abuse, violence, or loss. The persons affected

show symptoms of constant h yperarousal of the stress syst em

with inner unrest, anxiety, panic, sleep disorders, nightmares,

exhaustion, depression, and obsessive-compulsive behavior.

There are also physical symptoms of chronic tension that are

chronic pain in the mus culoskeletal system, bruxism, dental

defects, and headache (

Cloitre et al., 2013). Due to disorders of

the immune system caused by an impaired release of cortisol,

there is a high prevalence of infections, irritable bowel, and

other conditions (Boscarino, 2009). As a consequence of the

physical and mental exhaustion, ADHD-like symptoms (Kimbrel

et al., 2017

) such as distractibility, concentration disorders, or

procrastination can occur, which additionally can have an effect

on working capacity. The presence of trauma, flashbacks, and

avoidance behavior confirms the PTSD diagnosis.

The personality changes that lead to the diagnosis of a C-PTSD

are negative thoughts about t h emselves and others, mistrust, and

avoidance of social contacts.

The criteria for the diagnosis according to ICD/DSM are

adapted over time. A current discussion is the concept of

developmental traumatization. If the trauma is severe and

diagnosed at a late stage, in most cases, specialized psychotherapy

and usual medicinal treatment are required. Neurofeedback

offers in this study a promising additional benefit (

van der Kolk

et al., 2020; Micoulaud-Franchi et al., 2021).

PRACTICAL STEPS IN THE TREATMENT

OF PATIENTS WITH C-PTSD

The first step in the whole process takes place in the

psychotherapy practice. There is the need for a proper first

interview to gain a perspective on the history a nd background

of the patient and to determine which problems have priority.

It may be necessary to react with pharmacotherapy in the first

instance (sleep medicine, antidepressants, or anxiolytics), or to

initiate help with acute psychosocial problems by contacting

other doctors, family, employers, or insurance. In a further step,

it is important to move deeper into the special t rauma therapeutic

methods such as Imagery Reprocessing and Rescripting therapy

IRRT (

Grunert et al., 2007) or Eye Movement Desensitization and

Reprocessing EMDR (Shapiro, 1995). However, in many cases, it

is necessary to pursue mental (Lanius et al., 2017) and somatic

stability as a priority before working on the real trauma, and this

can be achieved using the neurofeedback as an additional next

step (

Panisch and Hang Hai, 2020). So the patients are informed

about this possibility and assigned to the psychosomatic therapist

to initiate the training (Gerge, 2020b).

The patients are informed about neurofeedback as a method,

about gained experiences, and the expect ed i mprovement as well

the possibility, in which within the first 10–15 sessions ups and

downs may occur. Based on this information, the shared decision

is made whether neurofeedback therapy is started or not. The

patient gets informed, that an evaluation will take place after

10–20 sessions to consider, whether the treatment is sufficiently

supportive or not.

In a further step, the medical, the personal, and the

family histories are elaborated on, as well as the current

symptoms’ presentation before we start. The assessment of

the individually important symptoms is conducted using a

computerized symptom questionnaire by EEG Expert called

“Symptomtracking” (https://eegexpert.net). It helps to rate the

severity of the relevant symptoms on a scale from 0 to 10. In

the course of the neurofeedback treatment, the symptom tracking

is repe ated every 2–3 months to be able to track the progress,

but also to be able to see in which domain more focus has

to be placed. The neurofeedback protocol priority is adjusted

accordingly (

Reiter et al., 2016).

The principal electrode placement used for trauma resolution

is T4-P4, which can be complemented or if necessary, changed

to T 3–T4 in case of instabilities, according to the Protocol

Guide 2017 by Sue Othmer. During the initial period of finding ,

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience | www.frontiersin.org 2 May 2022 | Volume 16 | Article 893830

Spreyermann Neurofeedback and Psychotherapy for C-PTSD

the optimal response frequency (ORF) to address the existing

symptoms such as hyperarousal, sleep disorders, flashbacks,

nightmares, anxiety, or muscle tensions, especially in pa tients

with high instability, ups and downs, and undesired side effects

can occur during the session, or within hours or days after the

session. These effects mostly last only for a few hours up to 1 or 2

days, and they help us to find the ORF (

Wiedemann, 2020).

After the ORF is found, it is important to find an optimal

rhythm for the sessions. One session per week is typical for an

outpatient setting; however, a biweekly rhythm can be better

tolerated. Regularity is of great importance, as the training

induces a process t hat ideally should not be interrupted, at least

not in the first 2 months.

Within this process, indications for additional sensor

placements can arise. The symptom tracking helps to monitor the

long-term course and also helps the patient to see progress and

stay motivated. Weekly communic ation with the psychotherapist

is of great importance to optimize the process for the patient.

When sufficient stabilization of the patient is achieved, trauma

confrontation may become easier. In a further step, synchrony

protocols (both in t he ILF and in the alpha band) may be

incorporated into neurofeedback therapy as an additional self-

regulation strategy. Synchrony training can also serve as a means

to assess the readiness to undertake alpha-theta training to

support the psychological reprocessing of the trauma (Imperatori

et al., 2017).

CASE PRESENTATIONS

In the following, two representative cases are elaborated to

illustrate t h e clinical process.

Case 1

Case 1 is a 40-year-old female suffering from C-PTSD caused

by th e violent death of her mother when she was around

20 years old. Over the years, there was psychotherapy with

various therapists, followed by around 10 years of psycho-

trauma therapy. Due to the residual hype rarousal, massive

sleep dysregulation, and nightmares, neurofeedback therapy was

advised. Sustained daytime flashbacks and dissociation were

reported by t he patient. In fact, the patient acted entirely

emotionless and absent. The answers were purely rational. In

contrast to the posture of “not-being-noticeable,” the patient

reports massive emotions such as fury, grief, helplessness,

anxiety, and panic being dissociated felt for her like dizziness. I n

addition, she was plagued by massive headaches, stress-induced

skin reactions, and tinnitus. The prehistory is heavily loaded,

growing up in a family full of conflicts, violence both emotional

and physical, a depressive and suicidal father, and a mother full

of sorrow about her drug-addicted brother.

There had been three suicides in the immediate family and

among c lose friends—she herself lost a close friend when she

was 5 years old, and at the age of 10, someone committed

suicide directly in her presence. Since childhood, she suffered

from poor sleep, nightmares, and restlessness in sleep. She had

daydreams about being adopted and her true parents coming

to rescue her. She had been ridiculed at school about her

skewed teeth as well as by her father. She withdrew and felt like

belonging nowhere. As a teenager, there were suicidal thoughts,

binge eating, and many illnesses. In her early 20s, the mother

died in violent death, and the father is also now de ceased.

Anniversaries of the deaths always increase the trauma-induced

symptoms, despite the passage of time. Looking at her childhood,

there are many consecutive events that led collectively to t h e

severe traumatization.

Neurofeedback Training and Symptom

Tracking

Due to a high emotional instability and very noticeable mistrust

and skepticism, T4-P4 was trained in the beginning. This calmed

down the patient. However, it also led to heavy side reactions such

as mood swings. For this reason, T3-T4 was added after session

7. After 25 sessions, T4-Fp2 was added. This protocol targets the

affective domain more directly. Again, there were panic states,

which were treated with T3-T4 for a few sessions. Now she is back

to a treatment solely with T4-P4 and alpha-theta.

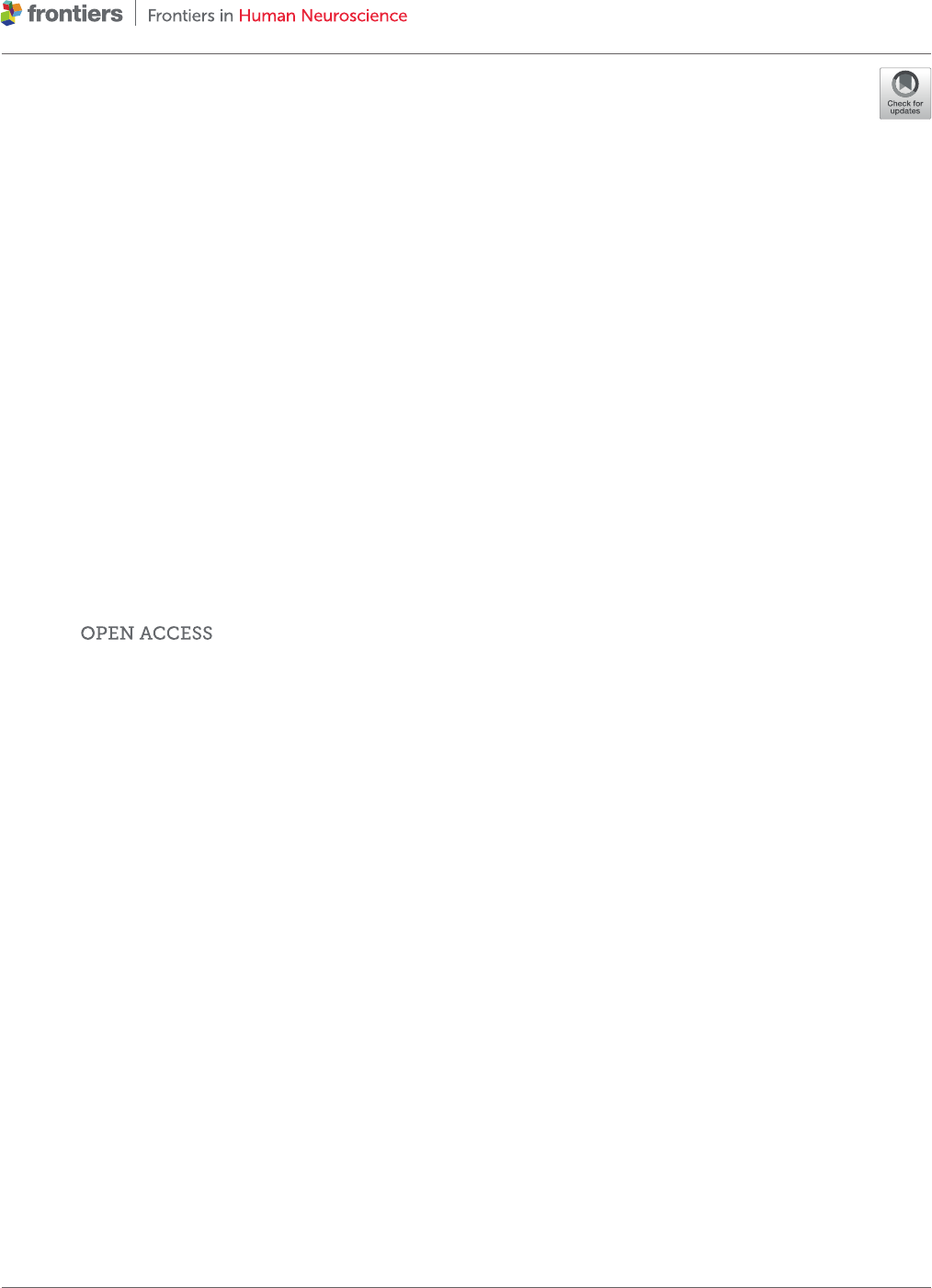

In Figure 1, the symptom tracking over the course of t ime for

the main symptoms is illustrated. The figure shows the steady

decline of symptom se verity to below 30% of the starting value,

over the course of 47 sessions. These symptoms had existed for

more than 20 years and could not be eliminat ed using medication

and psychotherapy.

In her own words, the patient describes herself as being back

to herself, back to the here and now, experiencing more placidity

and equanimity, and much better sleep.

The patient has now found her way back into life. She has

finished her dissertation, which she had started with panic attacks

and under hig h stress, without drama. She has found appropriate

employment. In the future, there is some work yet to be done

in terms of personal relationships. Due to the history of C-

PTSD and the ongoing personality changes, there is still a lot of

avoidance in her life, especially in terms of intimate relationships.

Case 2

Case 2 is the story of a 35-year-old female with C-PTSD. The

trauma dates back to early childhood. She was adopted as an

infant from the Far East by a German family with two children.

There was never the feeling of belonging to the family, and

this has persisted until the present. L ooking Asian while being

German, she has not found her real identity. This is one of the

reasons that she chose to start neurofeedback. The trauma was

triggered by continuous sexual abuse during primary school age,

but also from repeated relationships with heavy physical violence

by the partner, including brutal rape. As in the first case, the

trauma in this study cannot be traced back to a single event, but

rather to multiple insults. The patient suffers from permanent

and clear recognizable dissociation: her face looks mask-like and

her voice is t hin and unemotional. There is a steady twitching of

her eyelids due to flashbacks from violent scenes coming every

few seconds.

She has massive concentration and memory impairment,

making it impossible for her to work. Her sleep quality is

extremely poor; she awakes every few minutes; falling asleep

initially takes several hours. During the day, she is steadily

tired and exhausted. The only constant in her life has been her

daughter for whom she cares daily, cooks, goes horseback riding,

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience | www.frontiersin.org 3 May 2022 | Volume 16 | Article 893830

Spreyermann Neurofeedback and Psychotherapy for C-PTSD

FIGURE 1 | Time course of the different post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms of case 1 during 1 year of therapy, rated by the patient between 0 and 10.

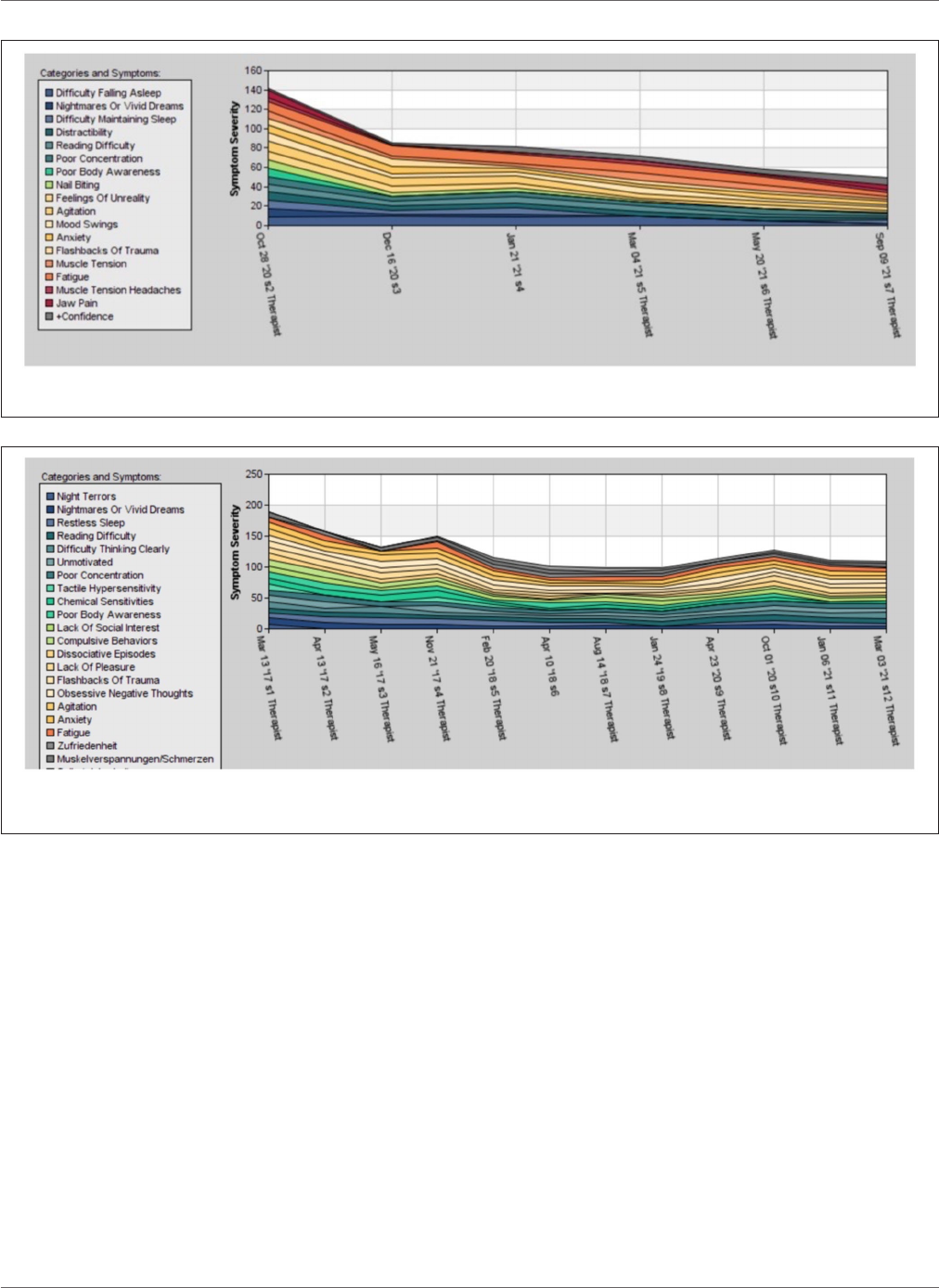

FIGURE 2 | Development of the PTSD symptom during the 5 years of therapy in case 2. The ups and downs are the results of reduction of medicaments, life events

such as divorce, and re-traumatization.

and much more. She has been doing neurofeedback treatment

for around 4.5 years now. It stands out since the beginning of

the NF training that in combination with psychotherapy, there

is a steady and very positive development, one that is not always

visible in symptom tracking. The first noticeable improvement

was enhanced sleep, which helped her in her daily life. She

could deal better with her household and learned how to play

golf to enhance her concentration and be more outdoors. After

2 ye ars, she relates that she is less dissociated, “which is not

always ple asant.”

In a second step, she was able to reduce the extensive

psychiatric medication; first, the neuroleptics, then, the

antidepressants, and lastly, the sleeping pills. The only thing left

is sleep-inducing antidepressants.

In further progress, there was the separation from her

pill-addicted husband, where the relationship had been very

destructive. Another relationship ended with a physical attack.

After being on her own for several years, she is now in a new

relationship. Psychotherapy helps her to learn the fundamentals

of a trusting relationship. She has even successfully managed to

build up a company of her own.

ILF Training and Symptom Tracking

The symptom tracking in Figure 2 shows that in the beginning,

there is a quick improvement in symptom severity followed by

fluctuations. In October 2020, there was a relapse caused by the

terminal illness of her father.

The treatment of he avily traumatized patients is not

straightforward, as the relationship is often characterized in the

beginning by high levels of mistrust, avoidance, and need for

control in the frame of the attachment trauma. When sleep

improved, she reduced her medication, which led to instabilities

and t he need to find a new ORF.

For a while, she wanted to be independent and, therefore,

stretched the frequency of the meetings to a maximum. She only

came when sleep got worse again after around 3-4 weeks. Since

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience | www.frontiersin.org 4 May 2022 | Volume 16 | Article 893830

Spreyermann Neurofeedback and Psychotherapy for C-PTSD

there was no further improvement due to the irregular training,

more intensive training was resumed. After 2 years, consecutive

new placements were added to T4P4, and now training on all

four basic sites is possible (T4-P4, T3-T4, T4-Fp2, and T3-

Fp1). Fp1-Fp2 training helps to reduce compulsive behavior and

racing thoughts.

In her own words, the patient asserts that before the

neurofeedback treatment, she had to take the strongest

medications and yet was unable to sleep well at all. Now, after 2–3

years of neurofeedback therapy, she sleeps more profoundly for

more hours and experiences a better sleep quality. She says that

she is no longer afraid of going to bed. In addition, she describes

that she feels her body again—where earlier she had a feeling of

numbness and her body had not been present in her thoughts.

An Overall Appraisal of Clinical Results

A quantitative appraisal of clinical effectiveness in the manner

of a formal retrospective study is not appropriate, given the

heterogeneity of the clinical population, as well as variety

of measures taken with each patient. However, looking back

qualitatively over the past 7 years, th e combination of trauma-

based psychotherapy and ILF neurofeedback has led to surprising

and motivating results.

For approximately 25% of the patients, there was an initial

improvement of the symptoms, but in the course of the therapy,

there was a stagnation of progress. In these cases, the addition or

adoption of other methods such as mindfulness training, HRV-

training, sports, or respiratory therapy should be considered.

In only 2 of 80 patients has there been no positive reaction to

the neurofeedback.

For around 15% of the cases, premature abandonment

of the t herapy was recorded, which can be traced to a

variety of reasons, which is common in the domain of

psychotherapeutic treatments.

However, for the rest of the patients with C-PTSD, good or

very good progress was observed. A n improvement of 60% up

to over 90% could be seen in symptom tracking, which is very

surprising given the severity of the initiating traumas and the

long-established symptom history of the patients.

Infra-low-frequency neurofeedback is emerging as a

promising method to help patients with PTSD. Both case

reports show that people who suffered a great deal and who

were not able to live a normal life were able to go back into

daily routines with the help of neurofeedback therapy. Even

though not all patients benefit, the strong likelihood of a positive

outcome is promising. One also must keep in mind that in

many cases, patients start neurofeedback therapy after having

already suffered a long time and having tried several therapies

without success.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The original contributions presented in the study are included

in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be

directed to the corresponding author/s.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from t he individual(s)

for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or d ata

included in this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The author confirms being the sole contributor of t hi s work and

has approved it for publication.

FUNDING

Open access fees are covered by the Brian Othmer Foundation,

6400 Canoga Ave., Suite 210, Woodlands Hill, CA 91367.

REFERENCES

Boscarino, J. A. (2009). Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results

from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1032, 141–153

doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.011

Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., and Maercker, A. (2013).

Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PT S D and complex PTSD: a latent profile

analysis. Euro. J. Psychotraumatology 4:20706.

Gerge, A. (2020a). What neuroscience and neurofeedback can teach

psychotherapists in the field of complex trauma: Interoception,

neuroception and the embodiment of unspeakable events in treatment

of complex PTSD, dissociative disorders and childhood traumatization.

Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation, 4:100164. doi: 10.10 16 /j .ejtd.2020.

100164

Gerge, A. (2020b). A multifaceted case-vignette integration neurofeedback and

EMDR in the treatment of complex PTSD. Eur. J. Trauma Dissoc. 4:100157.

doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100157

Grunert, B. K., Weis, J. M., Smucker, M. R., and Christianson, H. F. (2007).

Imagery rescripting and reprocessing therapy after failed prolonged exposure

for post-traumatic stress disorder following industrial injury. J. Behav. Ther.

Exp. Psychiatry. 38, 317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.005

Imperatori, C., Della Marca, G., Amoroso, N., Maestoso, G., Valenti, E.

M., Massullo, C.h., et al., (2017). Alpha/theta neurofeedback increases

mentalization and default mode network connectivity in a non-clinical sample.

Brain Topogr. 30, 822–831. doi: 10.1007/s10548-017-0593 -8

Kimbrel, N. A., Wilson, L. C., Mitchell, J. T., Meyer, E. C., DeBeer, B.

B., Silvia, P. J., et al., (2017). ADHD and nonsuicidal self-injury in

male veterans with and without PTSD. Psychiarty Res. 252, 161–163.

doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.015

Lake, J. H. (2015). The integrative management of PTSD: A review of conventional

and CAM approaches used to prevent and treat PTSD with emphasis on

military personal. Adv. Integr. Med. 2, 13–23 doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2014.10.002

Lanius, R., and Frewen, P. (2015). Healing The Traumatized Self. New York,

London: W. W. Norton and Company.

Lanius, R. A., Frewen, P. A., Tursich, M., Jetly, R., and McKinnon, M. C.

(2015). Restoring large-scale brain networks in PTSD and related disorders:

a propos al for neuroscientifically-informed treatment interventions. Eur J

Psychotraumatol. 6,27313. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.27313

Lanius, R. A., Nicholson, A. A., Rabinello, D., Densmore, M., Frewen, P. A., Paret,

C.h., et al., (2017). The neurobiology of emotion regulation in posttraumatic

stress-disorder: Amygdala downregulation via real-time fMRI neurofeedback.

Hum Brain Mapp. 38, 541–560. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23402

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience | www.frontiersin.org 5 May 2022 | Volume 16 | Article 893830

Spreyermann Neurofeedback and Psychotherapy for C-PTSD

Micoulaud-Franchi, J. A., Jeunet, C., Pelissolo, A., and Ros, T. (2021). EEG

neurofeedback for anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorders: a

blueprint for a promising brain-based therapy. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2384.

doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01299-9

Othmer, S. F. (2017). Protocol Guide for Neurofeedback Clinicians. 5 Edn. Los

Angeles, CA: EEG Institute.

Othmer, S. F., and Othmer, S. (2017). Rhythmic Stimulation Procedures in

Neuromodulation, editors Evans, R.E. and Turner, R. A. San Diego: Academic

Press. p. 225–278

Panisch, L. S., and Hang Hai, A. (2020). The effectiveness of using neurofeedback

in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Trauma

Violence Abuse. 21, 541–550 doi: 10.1177/1524838018781103

Reiter, K., Andersen, S. B., and Carlsson, J. (2016). Neurofeedback treatment

and posttraumatic stress disorder: effectiveness of neurofeedback on

posttraumatic stress disorder and the optimal choice of protocol.

J Nerv Ment Dis, 204, 69–77 doi: 10.1097/NMD.00000000000

00418

Shapiro, F. (1995). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Therapy: Basic Principles, protocols, and Procedures. New York: Guilford Press

van der Kolk, B. A., Hodgon, H., Gapen, M., Musicaro, R., Suvak,

M. K., Hamlin, E., et al., (2 01 6). A randomizes controlled study

of neurofeedback for chronic PTSD. Randomized Controlled

Trial>PLoS. 11,e01166752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.016

6752

van der Kolk, B. A., Rogel, A., Loomis, A. M., Hamlin, E., Hodgdon, H., and

Spinazzola, J. (2020). The impact of neurofeedback training in children with

developmental trauma: a randomized controlled study. Randomized Controlled

Trial > Psychol Trauma. 918–929 doi: 10.1037/tra0000648

Wiedemann, M. (2020). Neurofeedback in Clinical Practice in Restoring the Brain,

Neurofeedback as an Integrative Approach to Health, ed. H. Kirk. 2nd edition.

Routeledge, New York. p. 56– 79.

World Health Organization (2022). ICD 11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics:

6B41 Complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Available online at: http://id.who.

int/icd/entity/585833559 (accessed February, 2022).

Conflict of Interest: The author declares that the research was conducted in the

absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a

potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of

the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in

this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or

endorsed by the publisher.

Copyright © 2022 Spreyermann. This is an open-access article distributed under the

terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution

or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and

the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal

is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or

reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience | www.frontiersin.org 6 May 2022 | Volume 16 | Article 893830