Frontiers in Veterinary Science 01 frontiersin.org

Owner expectations and surprises

of dog ownership experiences in

the UnitedKingdom

KatharineL.Anderson *

†

, KatrinaE.Holland

†

, RachelA.Casey ,

BenCooper and RobertM.Christley

Dogs Trust, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Although many owners are satisfied by dog ownership, large

numbers of dogs are relinquished annually, with an estimated 130,000 dogs

cared for each year by rescue organisations in the UK. Unrealistic ownership

expectations are a potential factor in the decision to relinquish and therefore

understanding what surprises owners about the realities of ownership and how

this meets their expectations is vital.

Methods: Using a retrospective cross-sectional cohort study design, as part of

Dogs Trust’s National Dog Survey 2021, owners were asked ‘what has surprised

you most about owning a dog?’ and to classify how their experiences had

compared with their expectations on a list of aspects of ownership as either more

than, less than or as expected. Free text responses (n= 2,000) were analysed

using reflexive thematic analysis in NVivo Pro (v.12 QSR) and a quantitative

summary of classified expectations (n=354,224) was conducted in R.

Results: Many aspects of ownership were reported to be as expected, however

a discrepancy between expectation and reality regarding some aspects was

revealed. The cost of vet visits was greater than expected for the majority of

respondents (52%), whilst other factors that often exceeded expectations included

buying/rehoming cost (33%) and amount of patience needed (25%). Damage to

furniture was less than expected for many (50%) as was damage to garden (33%).

From the thematic analysis, four themes were generated that reflected what

surprised owners most about ownership: emotional connectedness of human–

dog relationships; dog’s impact on human health/wellbeing; understanding what

dogs are like; and meeting the demands of ownership.

Conclusion: Overall these results aid our understanding of dog-human

interactions, highlighting the complexity of the dog-owner relationship which

may come with unanticipated costs. Whilst this study’s results are reassuring

given many aspects of ownership were as expected, and surprises were often

positive, some areas had greater impacts than expected, raising opportunities

for intervention, resources or support. The aim would be to manage owners’

expectations prior to acquisition or ensure these are more realistically met,

reducing the likelihood of negative welfare implications for both dog and owner.

KEYWORDS

dog, expectations, human-animal bond, pet ownership, dog acquisition

1 Introduction

Dogs are one of the most popular companion animal species across the world, including

in the UnitedKingdom where dogs are owned by an estimated one-quarter of adults (1).

Although many owners report satisfaction with their dogs and their relationships with them

(2), signicant numbers of dogs face negative welfare situations, such as relinquishment or

OPEN ACCESS

EDITED BY

Mika Simonen,

University of Helsinki, Finland

REVIEWED BY

Jo Hockenhull,

University of Bristol, UnitedKingdom

Otto Segersven,

University of Helsinki, Finland

*CORRESPONDENCE

Katharine L. Anderson

†

These authors have contributed equally to

this work and share first authorship

RECEIVED 01 November 2023

ACCEPTED 25 January 2024

PUBLISHED 07 February 2024

CITATION

Anderson KL, Holland KE, Casey RA,

Cooper B and Christley RM (2024) Owner

expectations and surprises of dog ownership

experiences in the UnitedKingdom.

Front. Vet. Sci. 11:1331793.

doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

COPYRIGHT

© 2024 Anderson, Holland, Casey, Cooper

and Christley. This is an open-access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The

use, distribution or reproduction in other

forums is permitted, provided the original

author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are

credited and that the original publication in

this journal is cited, in accordance with

accepted academic practice. No use,

distribution or reproduction is permitted

which does not comply with these terms.

TYPE Original Research

PUBLISHED 07 February 2024

DOI 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 02 frontiersin.org

euthanasia. Each year, in the UK, an estimated 130,000 dogs are cared

for by rescue organisations (3). Factors associated with dog

relinquishment are varied, including dog behaviour, owner ill-health,

relocation or housing issues, lack of time, and nancial costs (4, 5).

Another factor associated with some cases of dog relinquishment is

unrealistic or unmet owner expectations (4, 6). Unrealistic

expectations for ownership were cited as a main reason for adopters

returning dogs to shelters in 7 to 13% of cases (7, 8). Current evidence

indicates a variety of dog- or ownership-related aspects associated

with mismatched expectations. For instance, people adopting dogs

from a UK charity who found the work and eort in looking aer their

dog to bemore than they had expected had 9.9 times higher odds of

giving their dog back to the shelter than people who found the eort

required to beless than expected (9). Similarly, adopters returning

their dog to the shelter within the rst three months of adoption had

signicantly higher expectations for dog health and desirable

behaviour, as well as the development of the human–dog bond,

compared with non-returning owners (10). Excessive nancial costs

associated with dog ownership is another reported reason for

relinquishment that suggests a discrepancy between expectations and

reality (11).

Previous research has explored owner’s pre-acquisition

expectations. In a recent survey of UK puppy purchasers, the

misconception that some “designer crossbreeds” (e.g., Cocker Spaniel

X Poodle, the “Cockapoo”) are “hypoallergenic” and thus pose a

reduced risk to owner’s allergies was found to motivate owner demand

for the purchase of such “designer crossbreeds” (12). is nding

indicates potential risks to both dog and human welfare if owner

expectations regarding a dog’s hypoallergenicity are not met. Other

research suggests that owners of doodles (i.e., poodle hybrids, such as

the “Cockapoo”) underestimated the maintenance and grooming

needs of doodle dogs (13). Inadequate grooming can lead to

potentially serious dog welfare consequences (14). In another survey,

conducted in Australia, many prospective dog adopters anticipated

health benets of dog ownership to include increased walking (89%)

and physical tness (52%) (15). Respondents also expected

improvements to mental health, through greater happiness (89%), and

decreased stress (74%), loneliness (61%) and depression (57%). In the

same study, dog training and dog behavioural issues were common

expected challenges of dog ownership, anticipated by 62 and 50% of

respondents, respectively. Expectations of dog ownership are shaped

by experience and knowledge about dog behaviours and ownership

requirements (16). Furthermore, evidence indicates that people with

greater knowledge about animal care, health, behaviour, training and

costs have more realistic expectations about dog ownership (e.g., the

eort required) than people with less knowledge (17).

e relationship between the current perceptions of aspects of dog

ownership experience and owner’s prior expectations has not yet been

fully explored in a sample of current owners. Whilst there is an

existing body of research about owners’ expectations surrounding dog

ownership, there is a data gap regarding whether such expectations are

perceived to besubsequently met. Furthermore, recent acquisitions

during/since the COVID-19 pandemic has seen a potential increase

to the pet dog population, with negative fallout possible particularly

if dogs were acquired impulsively and/or with unrealistic expectations

of ownership (18). Understanding which aspects of dog ownership

surprise owners, and in what ways, is therefore a critical step in

addressing dog relinquishment and optimising welfare for both

humans and dogs. Using a sample of current UK dog owners, the

objective of this study was therefore to retrospectively explore dog

owners’ current perceptions of their expectations of dog ownership,

reecting on whether certain aspects of ownership were more, less or

equal to what they expected. is study also investigated demographic/

owner factor variables for their association with aspects that surprised

respondents. Furthermore, the qualitative analysis aimed to broaden

the scope of understanding of this topic, by identifying further aspects

of dog ownership that surprised owners and produce richer insights

into owners’ experiences.

2 Methods

Ethical approval for this study was granted by Dogs Trust Ethical

Review Board (reference ERB050).

2.1 Data collection

is study used a retrospective cross-sectional cohort design, with

an online survey used as the data collection tool. e “National Dog

Survey 2021”, developed by Dogs Trust, collected responses from dog

owners in the UK between 10th September to 25th October 2021. Full

survey methodology including tool development, study participants

and data collection has been previously described (19).

2.2 Data analysis

To explore dog owners’ reections on their expectations of dog

ownership a convergent mixed-methods study design inspired the

data analysis (20). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected in

parallel, analysed independently and then interpreted together in a

comparative and contrasting way. Data included within the qualitative

analysis were responses to the free-text survey question “What has

surprised youmost about owning a dog?”, whilst the quantitative

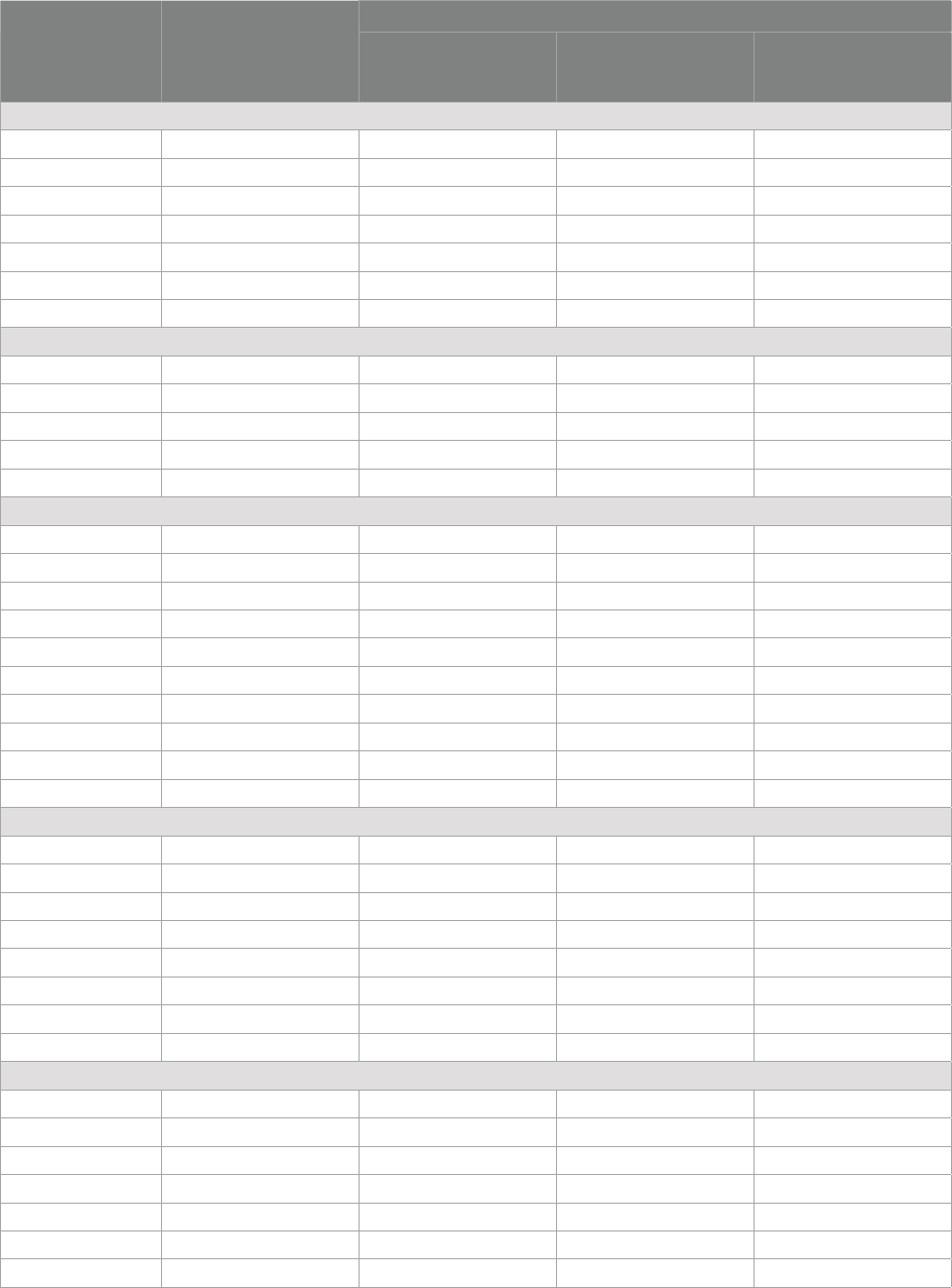

analysis summarises ndings from the question “Aer owning a dog,

please tell us which of the following are less, more or as youexpected?”

where respondents were asked to classify 13 functional areas of dog

ownership (Figure1) based on their experiences, as being “less than

expected”, “as expected” or “more than expected”.

2.2.1 Quantitative

Following the data cleaning methodology as described in

Anderson etal. (19), data were imported into R (version 4.1.3) (21)

and the distribution of the data checked. Descriptive statistics were

then collated based on responses to the question “Aer owning a dog,

please tell us which of the following are less, more or as youexpected?”,

and variables of interest were compared using the mean number of

surprises (combining both more than and less than expected

responses) cross tabulated to identify dierences between groups.

Variables of interest included age of the dog, due to the potential

dierences in experiences related to the current life stage of their dog,

as well as number of dogs in the household as presence of multiple

dogs may impact the comparison of expectations versus experience.

Due to the previous literature highlighting that younger owners may

bemore likely to experience unrealistic expectations of dog ownership,

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 03 frontiersin.org

owner age category was included within our analysis. Finally,

acquisition factors such as source of acquisition and price paid for dog

were included due to potential dierences in owners’ expectations

when acquiring their dog through dierent sources. Statistical

comparisons were considered inappropriate due to the large sample

size, increasing the likelihood of introduction of false positive results.

2.2.2 Qualitative

From the full dataset where answers were provided to the question

“What has surprised youmost about owning a dog?” (n = 273,899), a

random subsample of 2,000 free-text responses was generated in R

using slice_sample() from all comments that were not blank and

contained at least 3 characters. ese responses were imported into

NVivo Pro (v.12 QSR) and analysed following a reexive thematic

analysis approach (22, 23). e research question that guided the

qualitative analysis was “What aspects of dogs or ownership surprised

owners since their dog’s acquisition?” is closely resembled the free-

text question from which the data were obtained. An experiential

orientation to data interpretation was adopted as we aimed to

prioritise owners’ own accounts of their experiences and perspectives.

One author (KH) familiarised herself with the data by reading all

2,000 free-text responses, generating initial codes from the data and

then organising them into meaningful groups from which themes

were constructed. Data were inductively coded, in that coding was

driven by the content of the responses, rather than pre-determined

codes. As coding progressed, some codes were modied. From the

initial coding, categories were identied which were then collated into

themes. e themes linked ideas and concepts within grouped codes

that represented overall patterns of meaning that the researcher

interpreted from the data. Following the same process, another author

(KA) independently coded 1,000 responses from the subsample. is

was done not with the goal of achieving greater reliability or accuracy

between the coders, but rather to deepen our reexive engagement

with the data, for instance by identifying any overlooked areas in our

respective analyses. ree authors (KH, KA, and RMC) met to review

KH and KA’s construction of themes and relevant data references, and

collaboratively established the nal themes.

Whilst an inductive approach was employed for coding and theme

development, werecognize that the qualitative researcher always,

unavoidably, brings their pre-existing knowledge to the analysis. As

researchers in the eld of dog welfare research, both coders (and the

wider research team) were familiar with prior research on the topic

being explored. Most authors also had dog ownership experience.

We acknowledge that the team’s pre-existing knowledge and

experience may have informed our understanding of respondents’

experiences and the aspects they found surprising.

Including the full dataset within the qualitative analysis was

neither feasible, for manual coding, nor necessary, to meet the goal of

this study’s qualitative aspect. In line with research conducted within

a qualitative paradigm, the aim of this study’s qualitative analysis was

to explore some of the range and diversity of experience amongst dog

owners, rather than present a quantied representation of the data.

rough engagement with the subsample outlined above, including

appraisal of the breadth of the study’s aim and the richness of the

individual data items, the researchers determined that this subsample

size had adequate “information power” (24) to meet this study’s aim.

3 Results

A total of 354,046 respondents owning dogs in the UK completed

the survey. Respondents were asked to complete one survey per

household and for their most recently acquired dog. Full demographic

summaries of respondents are available in a previous publication (19).

3.1 Quantitative analysis

Respondents were asked to classify a series of statements based on

their current perception of ownership as either as “expected”, “less

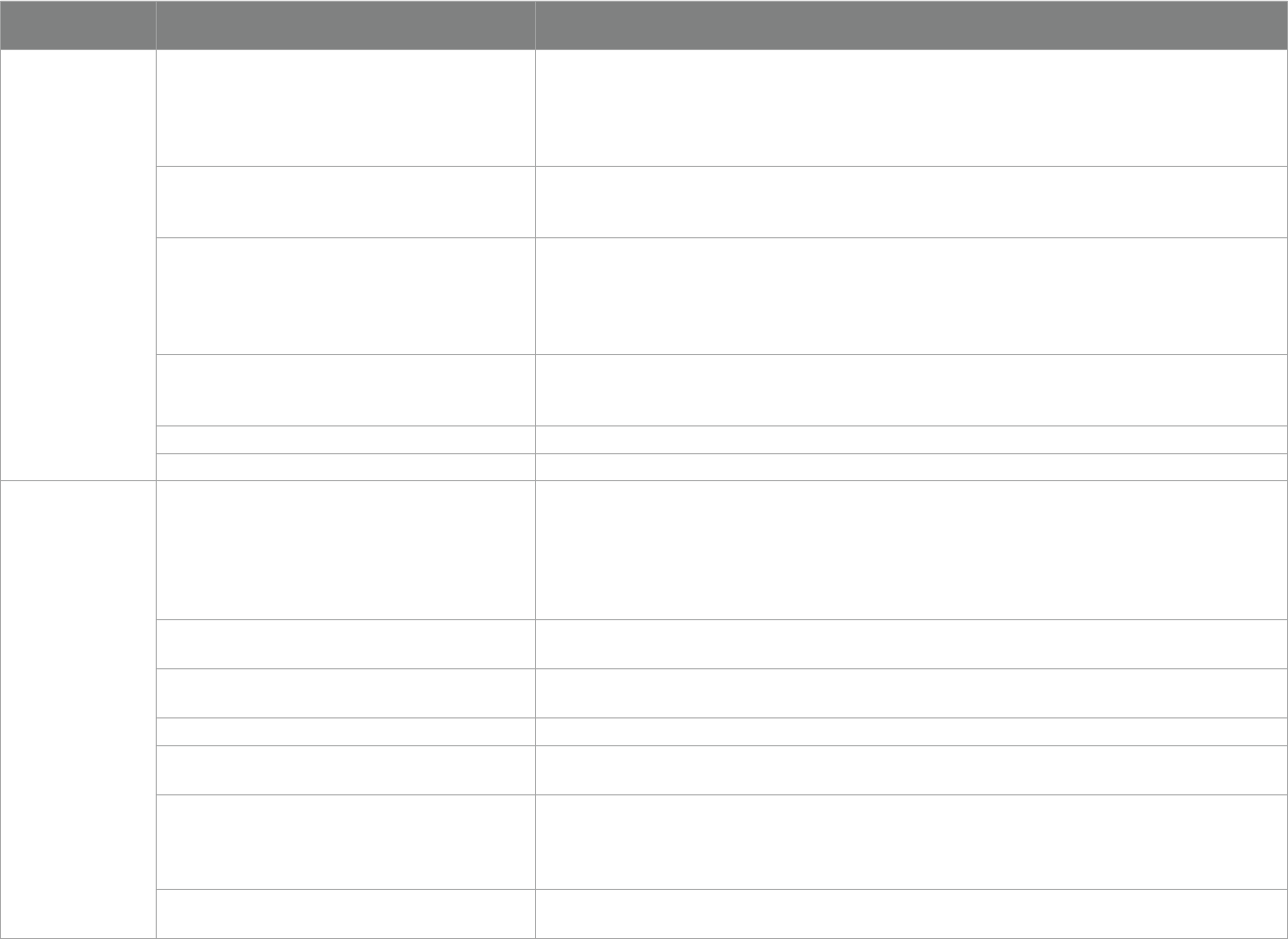

FIGURE1

Percentage of respondents (n = 354,046) stating that their expectations of dog ownership (based on a series of 13 statements) were either less than,

more than, or as expected.

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 04 frontiersin.org

than expected” or “more than expected”, with the overall results of this

study revealing insights in areas of ownership, indicating several

aspects of ownership in which owners reported that their expectations

were commonly under- or over-met (Figure 1). e greatest

discrepancies where expectations were exceeded were the cost of vet

visits (52% of respondents), cost of buying/rehoming a dog (32%) and

patience needed to deal with behaviour (25%). Areas that were oen

less than what was expected included damage to furniture and other

items (50%) and damage to garden (33%).

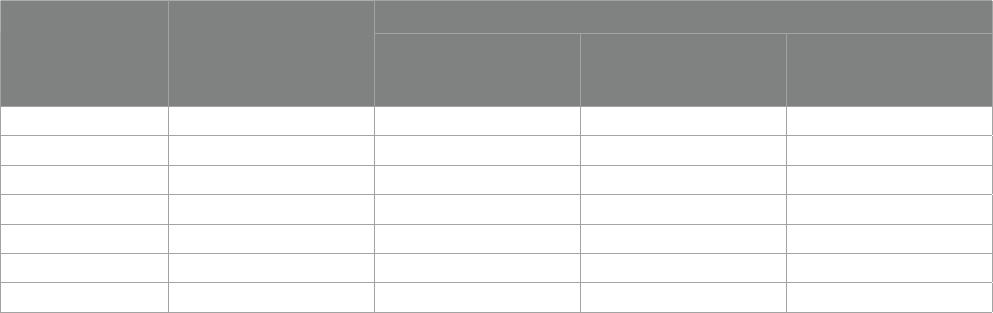

When considering the number of surprises experienced by

respondents, both “more than expected” and “less than expected”, the

mean number of surprises reported decreased steadily with an

increase in owner age category. Respondents in younger age categories

experienced a greater number of surprises, while older owners more

frequently reported ownership aspects were as expected (Table1).

Younger respondents more frequently reported surprises around:

amount of noise and activity, cost of feeding, and toys/beds, damage

to furniture, social life impacts, patience needed to deal with

behaviour, amount of mess, and time needed for exercise and training.

One exception was the cost of vet visits, which was reported to

be“more than expected” across all age groups; furthermore, the “more

than expected” surprise at cost of vet visits also was more frequently

reported as dog age increased.

A higher number of mean surprises was recorded in those who

owned fewer and younger dogs (Table1). ose with fewer dogs also

more frequently reported that damage to garden and furniture was

“less than expected”. Owners of younger (particularly 0–2 years) dogs

more frequently reported that damage to garden, amount of mess,

time needed for training and patience needed were “more than

expected” compared to owners with older dogs. e mean number of

surprises was also lower for owners who acquired their dogs from

rehoming centres, and higher in those getting dogs from general

selling or pet selling websites. ose who acquired their dogs from

rehoming centres also reported higher frequency of “less than

expected” than other sources.

Finally, those who paid more for their dogs had a higher mean

number of surprises and reported higher numbers of “more than

expected” within their responses (Table1). e amount of patience

needed to deal with their dog’s behaviour was reported as “more than

expected” more frequently by owners that had acquired their dog from

foreign rehoming websites or pet selling websites. Where owners had

acquired their dogs from websites, both pet and general sites, higher

frequencies of “more than expected” were reported by owners for:

more noise and activity, damage to furniture and garden, amount of

mess and mud in the house, and time needed for training compared

to other sources. Finally, owners sourcing their dogs from Kennel

Club websites reported number of vet visits to be “more than

expected” more frequently than owners who acquired their dogs from

any other source.

3.2 Qualitative analysis

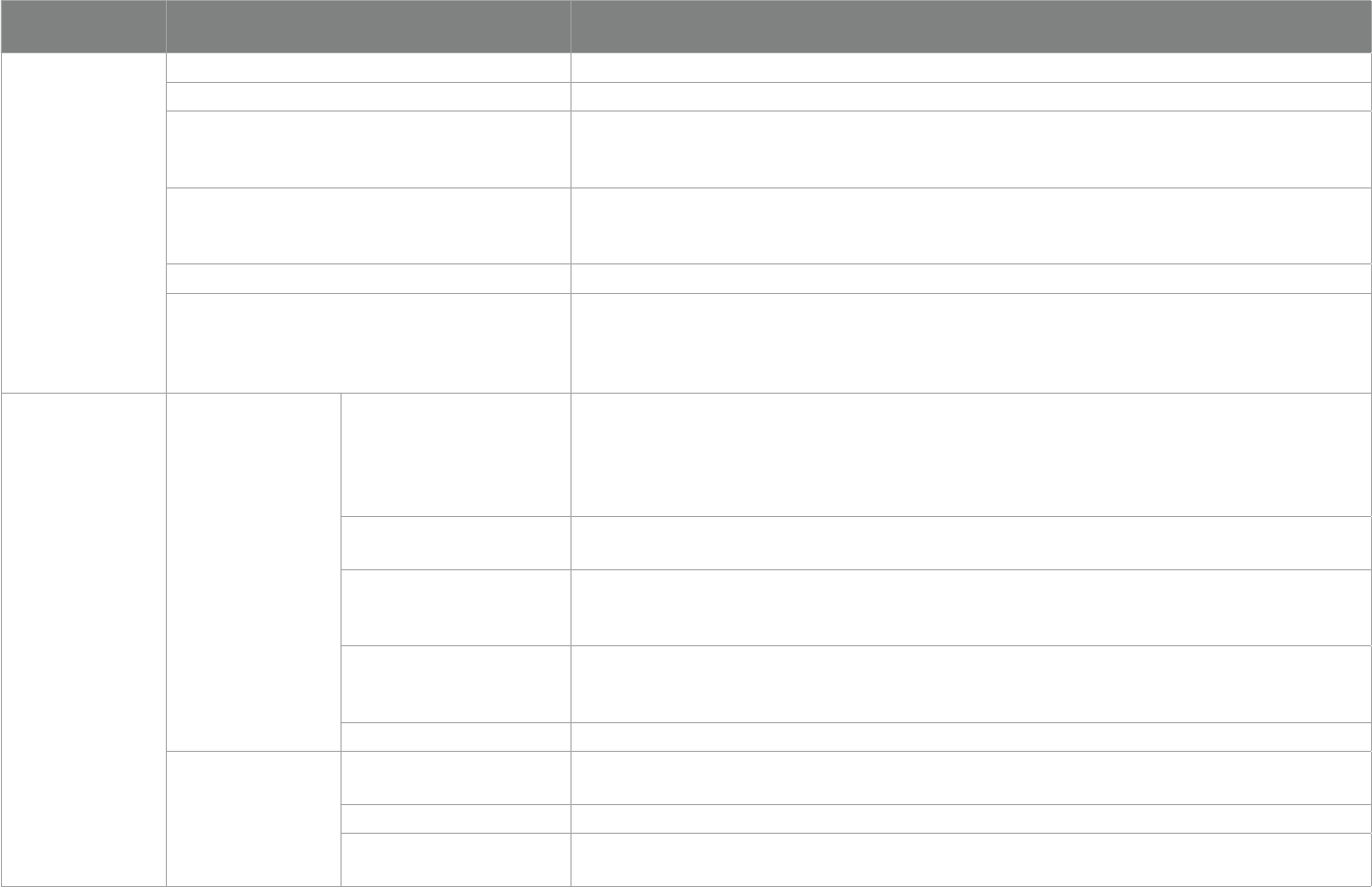

Of the codes generated from the responses, four distinct but

interlinking themes were constructed: Emotional Connectedness of

Human–Dog Relationships; Dog’s Impact on Human Health or

Wellbeing; Meeting the Demands of Dog-Ownership, and;

Understanding What Dogs are Like. Together, these themes reect

both emotional and practical dimensions of dog ownership and,

overall, illustrate that dogs occupied a more prominent place in their

owners’ lives than they had anticipated. e themes are outlined in

Table 2. Data excerpts contained in Table2 are referenced in the

written account below, to illustrate the themes. In addition to these

themes, some people commented that nothing had surprised them.

ese respondents oen linked their lack of surprise to their previous

ownership experience (e.g., “I have always had dogs so no surprises

really.”), suggesting that owners’ expectations are shaped, in part, by

their dog ownership history.

3.2.1 Emotional connectedness of human-dog

relationships

is theme encapsulates respondents’ surprise regarding the

intimacy of relationships established between themselves and their

dogs. One valued aspect of human-dog relationships, that surprised

some owners, was the company dogs provide (1a). Beyond occupying

a purely functional role in owners’ lives, however, many respondents

alluded to deeper human–dog relationships, commenting that they

enjoyed friendship with their dog (1b), or considered their dog to

be deeply embedded in the family unit (1c). Emphasising the

emotional bond they share with their dogs, some respondents

described the relationship with their dog as though the dog was akin

to a child (1d; 1e). Many owners expressed surprise regarding the

amount or depth of love and/or aection that they felt towards their

dog and/or that they received from their dog (1f; 1 g). e love that

dogs give their owner was oen valued for its “unconditional” quality

(1 h). Owners emphasised a few types of close relationships with their

dogs (e.g., friendship or family) that were oen described as

developing quickly (1i). Many owners described feeling more attached

to their dog than expected (1j), with some commenting that they miss

them when they are not together or that they cannot now imagine life

without their dog (or a dog) (1 k). Whilst some respondents focused

on the attachment they felt to their dog, others noted that this feeling

was reciprocal as they described a strong mutual bond between

themselves and their dog (1 l).

3.2.2 Dogs’ impact on human health or wellbeing

is theme encapsulates participants’ surprise regarding the

impact that their dog – or aspects of dog ownership – was perceived

to have had on the health or wellbeing of themselves or other people,

most typically a family or household member. Most references to

health or wellbeing highlighted positive perceived changes to

psychosocial aspects of health (i.e., mental, emotional, and social).

Many respondents referred to improvements, since dog acquisition,

in areas of mental health, including intrinsic positive feelings of

happiness or enjoyment (2a; 2b). Sometimes these outcomes were

associated with the time owners spent with their dog, including

through specic activities, such as walking (2b), or as a result of the

aection and love dogs give their owner (2c). Here, this theme

connects to the theme Emotional Connectedness of Human-Dog

Relationships. For some owners, dogs were felt to increase feelings of

ease (2c), mitigate loneliness (2d), and provide purpose or motivation

to get up or go outside (2e). Some respondents noted specic mental

health conditions that they felt their dog had helped to alleviate (2c;

2f). Responses suggested that, in some cases, the perceived

improvements to mental health may have been mediated (at least

partially) by the emotional support or comfort that dogs were widely

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 05 frontiersin.org

TABLE1 The mean number of surprises overall, and less than or more than, when classifying 13 statements about aspects of dog ownership as more

than, less than or as expected.

Mean number of surprises

Variable

Number of

respondents

Less than expected More than expected

All surprises (both

more than and less

than expected)

Owner age group (years)

18–24 17,423 2.64 3.27 5.92

25–34 46,273 2.22 3.05 5.27

35–44 52,775 1.78 2.70 4.48

45–54 96,723 1.69 2.45 4.14

55–64 90,272 1.68 2.31 3.99

65–74 43,450 1.84 2.22 4.06

75 or over 8,337 2.18 2.00 4.18

Number of dogs owned

1 256,892 2.09 2.56 4.65

2 96,727 1.44 2.48 3.92

3 19,188 1.26 2.34 3.61

4 5,713 1.24 2.33 3.58

5+ 3,446 1.16 2.11 3.27

Age of dog (grouped by years)

0 36,417 1.71 3.02 4.74

1 42,294 1.82 3.06 4.88

2 33,529 1.79 2.72 4.51

3 33,417 1.85 2.55 4.40

4 31,046 1.88 2.47 4.35

5 29,453 1.88 2.41 4.29

6 27,719 1.89 2.36 4.24

7 26,658 1.92 2.28 4.20

8 25,259 1.92 2.29 4.21

9+ 96,257 1.90 2.26 4.16

Price paid for dog

No cost/gi 49,460 1.95 2.32 4.27

Up to £100 27,398 1.98 2.18 4.15

£100–250 75,169 1.96 2.25 4.21

£251–500 79,672 1.83 2.47 4.30

£501–1,000 87,614 1.76 2.65 4.41

£1,001–2000 45,872 1.77 2.98 4.75

£2001–3,000 14,447 1.83 3.31 5.13

Over £3,000 2,417 1.97 3.30 5.27

Source of acquisition

Local press 6,618 1.76 2.34 4.10

Rehoming website 47,172 1.95 2.14 4.10

Rehoming visit 16,763 2.13 2.15 4.29

Breed group website 10,033 1.66 2.51 4.18

Breeder visit 21,799 1.82 2.47 4.30

Breeder website 13,131 1.82 2.61 4.42

Local community 8,982 1.84 2.46 4.30

(Continued)

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 06 frontiersin.org

reported to provide, particularly during dicult periods in a person’s

life (2 g; 2 h). Respondents were also surprised by the increase in social

interactions they had experienced as a dog owner, sometimes forming

social connections with other people through walking their dog (2i).

Dogs were described as acting as a catalyst for conversation with

strangers who they would not otherwise interact with (2j). As well as

interactions and connections with strangers, some participants

commented that their family dynamic had improved since acquiring

their dog, with the dog perceived to have brought family members

together (2 k). In addition to the emphasis that many respondents

placed on impacts on psychosocial health, some respondents also

highlighted benets to physical health, achieved through increased

exercise via walking (2 l).

However, some respondents expressed surprise at how they

perceived dog ownership to have compromised their wellbeing.

Worries about meeting their dog’s needs through optimising their

health and happiness were reported (2 m), with some suggesting that

their concerns were associated with their close relationship with, or

attachment to, their dog (2n). Respondents also related their

attachment to their dog with the emotional distress owners experience

as dogs age and die (2o). is aspect of this theme should thus

beinterpreted in conjunction with the theme Emotional Connectedness

of Human–Dog Relationships. A further threat to owner’s wellbeing

was the emotional strain associated with the oen-reported “hard

work” involved in raising a puppy or owning a dog with challenging

behaviour (2p), which was an aspect of the theme Meeting the

Demands of Dog Ownership.

3.2.3 Meeting the demands of dog ownership

is theme is characterised by respondents’ surprise regarding the

extent of dogs’ needs and how owners meet these. Meeting the

demands of ownership was described by respondents in two primary

ways: (1) through the provision of largely tangible things, for instance

time (i.e., time spent training or exercising) or money, and; (2) how

fullling their dog’s needs was associated with an all-encompassing

caregiving role performed by the owner. Together, these aspects reect

the practical and aective dimensions of meeting the demands of

dog ownership.

e rst aspect of this theme concerned owners’ surprise

regarding the extent of owner involvement or the amount of resources

required to full a dog’s needs. Some respondents emphasised their

surprise regarding the amount of time and attention dog ownership

involved (3a; 3b). For instance, owners noted that the amount of time

required to meet their dog’s training needs was greater than expected,

with some suggesting that they have found training to bean ongoing

process, rather than an activity that can befully completed (3c). For

some respondents, dog ownership had been greater or harder work

than anticipated, oen due to the amount of training or care required

(3d). An emphasis on more hard work was particularly expressed by

owners of puppies (3d) or rescue dogs (3e), with these owners

associating the hard work with inherent challenges they perceive to

accompany these types of dogs. However, several respondents

expressed that the hard work was worth it, given how rewarding they

found dog ownership to be(3f). As well as the demand on owner’s

time and eort, some respondents had not expected the nancial costs

associated with dog ownership to beso high. Veterinary costs were a

commonly reported surprising expense. Some owners perceived

veterinarians to begreedy (3 g), for instance by “upselling” procedures

(3 h) or charging more than owners anticipated for issues they

considered to beroutine or minor (3i). e cost of insurance was also

reported as surprising by a minority of owners, with some placing

emphasis on the rising cost of insurance as dogs age (3j).

In attempting to full their dog’s needs, some participants

emphasised the level of commitment (3 k) or responsibility that they

found to berequired of dog owners, or that they felt towards their dog.

A few respondents explicitly associated their sense of responsibility

with their desire to optimise their dog’s happiness (3 l) or meet their

training needs (3 m). Owners’ commitment to their dog’s wellbeing

led them to perceive their lives as being organised around their dog’s

needs. One consequence of this was a sense of restriction around

owners’ spontaneity, with some viewing their dog as a tie – for

instance, limiting their ability to travel (3n). A minority of respondents

also noted their surprise that society – particularly hospitality

businesses – is not always welcoming to dogs, adding to the additional

forward planning required when wanting to go out and about with

their dogs (3o).

3.2.4 Understanding what dogs are like

is theme encapsulates elements that comprise how dogs act, or

who they are perceived to beas individuals, primarily in terms of their

temperament, abilities and behaviour. One aspect that commonly

surprised respondents was the amount of personality or character their

Mean number of surprises

Variable

Number of

respondents

Less than expected More than expected

All surprises (both

more than and less

than expected)

Local adverts 2,024 1.91 2.40 4.31

Kennel club website 23,885 1.72 2.60 4.32

Foreign rehoming website 10,559 1.92 2.45 4.37

Family and/or Friends 68,926 1.91 2.50 4.40

General website 31,484 1.83 2.71 4.54

Social media 17,088 1.94 2.63 4.57

Pet website 79,786 1.80 2.86 4.66

TABLE1 (Continued)

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 07 frontiersin.org

TABLE2 Key themes from the thematic analysis relating to surprises associated with dog ownership when asked “What has surprised youmost about owning a dog?”

Themes and

definitions

Sub-themes Example data extracts

1. Emotional

connectedness of human-

dog relationships: owners

were surprised by the

quality and depth of

relationships formed, and

interactions experienced,

between themselves and

their dog

Companionship dog provides “How much Ivalue her company.” (1a)

Friendship between human and dog “How Itruly consider him to beone of my best friends.” (1b)

Dogs as part of the family

“How much of a vital role in the family they play.” (1c)

“How attached youget, they become your children.” (1d)

“[Dog name] is the most demanding yet aectionate dog I’ve ever owned, he’s like a child.” (1e)

Love and aection between human and dog

“I never imagined that Icould love the way Ilove [dog name].” (1f)

“How much love and aection they have to show you.” (1 g)

“e love they give is pure and unconditional.” (1 h)

Ease or speed of relationship forming “How quickly youfall in love with him and how quickly hebecomes part of the family.” (1i)

Attachment between human and dog

“I never in a million years realised how attached Iwould get to a dog. I’ve owned cats before but never had the emotional attachment like this.”

(1j)

“How attached ive [sic] got to him, could not imagine not having him.” (1 k)

“e unbreakable bond between me and my dog.” (1 l)

2. Dog’s impact on human

health or wellbeing:

owners were surprised by

the eect their dog, or dog

ownership, has had on

their health or wellbeing

Dog improves health or

wellbeing

Dog makes owner feel good

“I got more happiness than what Ithought Iwould get, seeing him gain condence and learn is very rewarding.” (2a)

“How calm Ifeel and the enjoyment Iget from a long walk.” (2b)

“How much calmer Iamjust being with them cuddles on the sofa, or just sitting together helps my anxiety.” (2c)

“How Ido not feel lonely anymore.” (2d)

“[G]ive me a reason to get up even on the toughest days.” (2e)

Mental health conditions improved

through dog

“e way it changed the whole family hehelped my daughter immensely as she suers with anxiety and depression.” (2f)

Emotional support or comfort dog

provides

“How much [dog name] has comforted me when my parents passed away.” (2 g)

“e impact hehas on everyone who spends time with him. Wehave a friend who asked to spend time with [dog name] as it helped him through

a dicult time.” (2 h)

Social interactions or connections

through dog

“e friends Ihave made from walking the dogs.” (2i)

“[T]alking to strangers because they do not treat youlike your [sic] odd when youhave got a dog with youand youtalk to them.” (2j)

“How hehas united our family.” (2 k)

Physical health has benetted “[I]mproving my tness via walking.” (2 l)

Dog puts a strain on health

or wellbeing

Worries about their dog

“e emotional drain of worrying about how to help my dog best and what more could Ibedoing to help her.” (2 m)

“How much Iwould fall in love with him, but also how much then Iworry about him too.” (2n)

Heartbreak when they pass away “How devastating it is to lose them its [sic] like losing family.” (2o)

Emotional strain of dog’s behaviour

or training

“As our second dog [dog name] has been hard work compared to our previous boy to the point of considering rehoming him. Been soul destroying

at times.” (2p)

(Continued)

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 08 frontiersin.org

Themes and

definitions

Sub-themes Example data extracts

3. Meeting the demands of

dog-ownership: owners

were surprised by the

amount of time, work,

eort or money involved

in caring for their dog,

and how meeting their

dog’s needs aects their

everyday life

Dog ownership is time consuming

“e amount of time required to spend with your dog e.g. [sic] Walking, playing, training etc.” (3a)

“Having only had one dog before, a fourteen year old male mixed breed, and gone into owning a puppy with my eyes open, Ihave still been

surprised at how totally full on she is, needing to bewatched every waking minute, in or out of the house! Also, If it’s within reach, it will bein her

mouth.” (3b)

“How dicult puppies are to look aer and how much constant training they need.” (3c)

Dog ownership can behard work

“Puppy training is very hard work when the puppy has not got an older dog to learn from.” (3d)

“[H]ow challenging it can beto have a rescue dog.” (3e)

“How much work it is but how much youget out of it.” (3f)

Dog ownership is expensive

“Owners since 1989 […] Vets have gone very greedy.” (3 g)

“e behaviour (selling up techniques) of vets, e.g. Routine drip following minor surgery plus pre-op blood tests for puppy tooth extraction and

stitches.” (3 h)

“e unexpected costs of vet fees and how everything seems to bea £100 minimum for even just a simple ear infection.” (3i)

“Worst thing insurance is a nightmare especially when your [sic] dog is getting old.” (3j)

Commitment and responsibility towards dog

“[T]he commitment as wecannot leave him.” (3 k)

“How much responsibility Ifeel towards his happiness.” (3 l)

“e responsibility to train and teach.” (3 m)

Everyday life organised around dog “It is very tying and doing normal things like going out or arranging holidays need much more thought.” (3n)

Society is not always dog-friendly “[H]ow many places aren’t dog friendly.” (3o)

4. Understanding what

dogs are like: owners were

surprised by what dogs

are like, including aspects

of dog’s temperament,

behaviour or abilities

Dogs’ personality or temperament

“His personality—it’s HIUUGE!” [sic] (4a)

“How loyal and loving they are.” (4b)

“I have had dogs all my life but never had a Labrador it delights me that how friendly our dog is.” [sic] (4c)

“[H]ow much fun they are.” (4d)

“I have had many dogs but this one is so good she has never chewed or eaten anything she is not allowed.” (4e)

“e only thing that surprised me is the dierent temperaments of dierent breeds and Ilove how each dog has its own unique personality.” (4f)

Dog’s energy or activity levels

“is has been the most energetic puppy Ihave ever owned. My last doodle was very calm.” (4 g)

“How much she sleeps during the day!!” (4 h)

Dogs’ intelligence

“[Dog name] is dierent from all the others iv [sic] had, in that in human terms, Ithink heborders on being a genius, icant [sic] believe how easy

to train hewas.” (4i)

Communication between humans and dogs “How astute dogs are. ey know when youare upset or need reassurance and give it to you(all mine have).” (4j)

Dog’s ability to transform

“Considering [dog name]’s rescue background when werehomed her at 4 months old how well she has adapted to life with us and how lovely and

trusting she is with people and other dogs.” (4 k)

Dog’s behavioural problems

“He’s a sweet dog with a lovely personality, but his barking can upset people and other dogs.” (4 l)

“Howling when Ileave him even for short periods. My previous dog had no problem being le alone.” (4 m)

“e initial puppy teething stage was a real big shock!” (4n)

“e 6 month old (adolescent) regressive behaviour. Heseems to bepushing boundaries and forgetting all that he’s learnt with training.” (4o)

Dogs are dirty or messy

“How much bloomin [sic] hair this dog has and leaves everywhere on my carpet.” (4p)

“How much hepoos and how bad his trumps smell.” (4q)

TABLE2 (Continued)

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 09 frontiersin.org

dog has (4a). Specic personality traits noted were predominantly

positive, including loyalty (4b), lovingness (4b), sociability or

friendliness (4c), and fun (4d). Some respondents were surprised by

how well-behaved their dog is (4e). ere was an emphasis on dogs’

individuality as an aspect that surprised people, with some commenting

on dierences between dierent dogs’ temperaments (4c; 4e; 4f). As well

as the individuality of dogs, some respondents reported their surprise

regarding perceived breed-based dierences in temperament (4f). A

further aspect that surprised some owners was their dog’s activity or

energy levels. A few people with previous ownership experience

commented on the dierence between energy levels in their current and

formerly owned dogs (4 g). A small minority of respondents were

surprised by the amount of time their dog spends sleeping (4 h).

Some respondents were surprised by how intelligent they

perceived their dog to be, sometimes inferred from their dog’s ease of

learning (4i). As well as general intelligence, dogs’ communicative

abilities with people were also noted, with some owners commenting

on their dog’s remarkable ability to understand and respond to human

emotions and moods (4j).

A dog’s ability to adapt to their new surroundings surprised some

respondents, particularly those who had adopted their dog (e.g.,

acquired from a rehoming organization). Some were surprised by how

well or quickly their dog had settled in (4 k).

However, some aspects of dog temperament or behaviour were less

positively regarded, as some respondents reported being surprised by

elements of their dog’s behaviour they considered problematic. A range

of specic issues were noted, including barking, which a minority of

participants reported was a problem either for themselves or others

(4 l). Separation-related behaviours (e.g., crying when le home alone)

surprised a few others (4 m). A minority of respondents commented

on behavioural issues associated with puppies, including puppy

teething or biting (4n) and behavioural regression during adolescence

(4o). Dog’s individuality was highlighted in some owners’ accounts of

behavioural issues, whereby individual dogs had been more or less

challenging than other dogs owned by the respondent (4 m).

A minority of participants were surprised by the messy and dirty

aspects of their dog or dog ownership. e amount of hair that dogs

shed was a commonly reported issue, with some respondents

describing dog hair as ubiquitous in the home (4p). Some respondents

reported aversion around their dog’s bodily functions, for instance

referring to the amount of poo the dog produces (4q).

4 Discussion

e aim of this study was to explore how the experience of dog

ownership compared with owner expectations in a sample of UK dog

owners. Overall, the results of this study provide initial insights into

certain areas of expectations surrounding dog ownership where

owners may experience discrepancies and surprises related to dog

ownership. e ndings highlight several aspects of dog ownership

that surprised owners in both positive and negative ways, which can

beutilised to guide future research in this area as well as develop

interventions aimed at supporting dog owners to reduce the likelihood

of negative fallout, such as relinquishments, due to these discrepancies.

One key area of surprise for owners within this study was around

meeting the demands of dog ownership, which encompassed both the

extent of dogs’ needs and the capability of owners to meet these. is

was identied through both the qualitative thematic analysis and the

quantitative analysis of graded statements. Within this theme, it was

common for respondents to besurprised by factors related to costs

associated with dog ownership. Common ndings within this study

were unexpected costs relating to the care of the dog, such as feeding

them, providing necessities such as beds and toys, and keeping them

healthy. Previous research has also demonstrated that unexpected or

excessive nancial costs are perceived as a challenge in dog ownership

(15). Within the quantitative data, the greatest surprise reported by

owners was the costs related to veterinary care, with owners reporting

this more frequently as the age of the dog increased, suggesting unmet

expectations can occur some distance in time from acquisition. is

increase in surprise of vet costs in owners of older dogs may either

reect a perceived increase in the costs associated with health

conditions particularly prevalent in older dogs, or a wider perceived

increase in service costs over time. is was also a key sub-theme

within the qualitative analysis where many were surprised at the cost

of care, particularly things they themselves considered minor or

routine. is suggests that some owners may perceive veterinary

surgeries to beovercharging or proteering, when in reality many

veterinary procedures, including routine ones, are cost intensive. With

the UK’s funded public health system, owners may beunlikely to

compare veterinary healthcare costs to that of a human healthcare

setting, raising the question as to how owners benchmark veterinary

costs. Research from the UnitedStates suggests that pet owners and

veterinarians may dier in how they relate to veterinary costs (25).

When discussing the costs of veterinary care in focus groups, pet

owners suggested that animal care should come before prot, while

veterinarians focused on the tangible aspects of their services (e.g.,

time) and felt that their work is undervalued. While some existing

research in other countries has explored public perceptions of the

veterinary profession (26), there is a lack of evidence pertaining to UK

pet owners’ perceptions of the veterinary profession. Further research

into public perception of the veterinary profession and the

veterinarian-client relationship in the UK would be benecial to

understand this further, as well as to better understand cost-related

barriers to obtaining veterinary care and ways to mitigate these. Breed

can also impact on expectations of costs, with owners of brachycephalic

breeds more prone to underestimate the veterinary cost of their dog

due to the high disease burden seen in these breeds (27). Financial

burden may occur where expectations of costs are exceeded. With

nancial reasons oen reported as factors associated with the

relinquishment of pets (28–30) and in particular cats and dogs, it is

important that owners are aware of and understand the potential

lifetime nancial costs, particularly routine costs, involved in dog

ownership prior to acquisition.

Successful human-dog relationships oen rely on met expectations,

with ownership oering a symbiotic relationship for both dogs and

their owners. As part of this relationship, it is imperative that owners

invest the necessary time to provide their dogs with what they need, for

both their dog’s welfare and their own, with research highlighting

owners may experience negative wellbeing due to feeling they had not

met their dog’s needs or expectations (31). Within this study, another

area of surprise was the amount of time and eort needed to provide

the necessary care for a dog. Oen owners felt like their lives were

organised around their dogs to full their dog’s needs, and the level of

commitment and responsibility was oen noted as a surprise.

Misconceptions of the amount of time needed for elements such as

exercise and training may exist, particularly to those who may not

conduct sucient research before acquiring their dog or acquire a dog

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 10 frontiersin.org

ill-suited to their lifestyle. A common owner-related reason for

relinquishment of dogs is due to lack of time to spend with the dog, not

being able to provide the time they need (15, 32–34), whilst studies also

highlight the increase in responsibility as a challenge of dog ownership

(15, 27, 33). Scarlett etal. (34) found this was most common for owners

of younger (less than 2 years) dogs, with 70% of owners having owned

their dog less than a year, suggesting that in many cases this may bedue

to unrealistic expectations of time requirements, rather than changes

of circumstances. Misconceptions of what specic breeds need has also

been highlighted, with a study highlighting that owners of

brachycephalic breeds were commonly surprised at the level of exercise

and maintenance their dogs required (27).

Training is an important element of dog ownership and, within this

study, the amount dogs needed oen exceeded their owners’ expectations

and there was surprise that this was a continual ongoing process and

need throughout the dog’s entire life. Problematic behaviours are

common reasons for relinquishment, posing signicant concern and

challenges to dog owners (15, 17, 31, 33, 34) and without adequate

training and appropriate behaviour modication, subsequent undesirable

behaviours may develop. Some aspects of dog behaviour were reported

negatively by respondents with many owners being surprised by their

dog’s problematic behaviour. is included issues such as separation-

related behaviour and barking. Previous research has highlighted that

dogs that behaved in unexpected ways resulted in reduced emotional

closeness and attachment to dog – highlighting potential damage to the

human-animal bond if expectations are not met (27). Furthermore,

many owners were surprised by the amount of attention their dog

needed, as well as the amount of patience; this was particularly true for

those owning puppies and rescue dogs. While this unmet expectation

has the potential to jeopardise the human-animal bond, for many the

hard work was however worth it due to the rewards of ownership.

Another key nding of this study was the surprise that dog owners

had around understanding what their dogs are like. When asked to

construct their “ideal” dog, in a study by King etal. (35), owners

reported a number of physical and behavioural traits that were

important to them. is included traits such as friendliness and

obedience, with women preferring traits such as calm and sociable and

men selecting traits such as energetic and faithful. Evidence further

suggests owners acquire dogs to provide a source of companionship,

and therefore likely select a breed reported to oer a suitable personality

and temperament to match their expectations (15, 36, 37). Despite this,

within our research many respondents were surprised by elements of

the way their dogs were with regards to their individual personalities

and temperament, how much character they had, as well as their levels

of activity and energy. It was also common for owners to report

surprises when comparing their current dog to previously owned dogs,

such as dierences in temperament and energy levels. Research has

shown owners may bemore likely to return/relinquish a dog when

comparing them to a previously owned dog’s needs and traits, due to

being less tolerant of what they may consider misbehaviour (15). Dog

needs and behaviour can both vary greatly between and within breeds

(38, 39), and therefore expecting dogs to behave similarly to previously

owned dogs, particularly if the same breed, may result in unrealistic

expectations and ultimately negative outcomes.

e qualitative analysis provided deeper insight into factors not

captured by the quantitative data in this study, such as the emotional

connectedness of the dog-owner relationship, which was oen

reported as a surprise by owners. Existing literature suggests that

companionship is a commonly expected benet of dog ownership

(15), with numerous studies reporting that companionship for the

owner is a primary motivation for dog acquisition (37, 40–42).

Companionship for others in the household (including children,

adults or dogs) is another common reason for getting a dog (37).

erefore, this study’s qualitative ndings indicate that the perceived

amount and depth of companionship provided by dogs may beeven

greater than expected. Similarly, whilst previous research has found

that dogs are oen understood as family members (36, 43–49) and

that, in Britain, pets have been considered as friends since the end of

the 17th century (50), the closeness of owner-dog relationships

nevertheless surprised many of our respondents.

Consistent with previous literature (47, 51) respondents associated

strong human-dog attachments with the emotional support or

comfort they perceived their dogs as providing them with. Whilst

evidence indicates that prospective owners oen anticipate mental

and physical benets (15, 36), many respondents in this study reported

these as taking them by surprise, suggesting that this is another aspect

of ownership that may be dicult to fully comprehend prior to

acquisition. Despite owners’ surprise regarding the emotional benets

of dogs or dog ownership, this study’s qualitative ndings also

highlighted some respondents’ surprise around the more unpleasant

emotions associated with dog ownership. Feelings of worry and guilt

about whether they were suciently meeting their dog’s needs took

some owners by surprise. is perceived negative impact of ownership

on owner wellbeing has been similarly identied in previous research

(51). Perceptions of pets as a source of worry were highlighted in

studies of pet ownership experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic,

with owner’s worries oen linked to restricted access to veterinary

care, food supply chain issues, or exercise restrictions during this time

(52–54). Beyond everyday worries, owners in this study also reected

on their surprise regarding the emotional distress felt when dogs die.

Some respondents’ comments suggest that greater attachment with a

dog may bepositively associated with the severity of grief experienced

or anticipated when dogs die, which echoes ndings from previous

research (51, 55–58). Consistent with the contradictory ndings in

existing literature (51) our research suggests both positive and

negative perceived impacts of dog ownership on owner’s wellbeing

exist. Overall impacts of dog ownership (whether positive and/or

negative) on owner wellbeing is likely dependent on the individual

dog, owner and their unique relationship (51).

is study’s ndings showed that many aspects of dog ownership

were reported as surprising. Evidence suggests that around half of dog

owners carry out pre-acquisition research ahead of acquiring their dog

(59). It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that many owners report

elements of ownership as not what they expected. In those that do

conduct pre-acquisition research (and from appropriate sources), this

disparity in their expectations may be due to prospective owners

having diculty in fully comprehending the lived reality prior to

acquisition. In order to address this, interventions could include

physical preparations such as spending time caring for dogs, e.g.,

co-care of a friend’s dog/fostering, on top of the desk-based research

owners are encouraged to conduct before acquiring their dogs could,

in order to prepare owners for the realities of dog ownership. Further

research into expectations around dog ownership is warranted, as well

as assessing interventions aimed at encouraging pre-acquisition

research. Preparing owners ahead of acquisition of a dog may well aid

understanding around the process of acquiring a dog, and reduce the

likelihood of negative fallout such as decreased welfare, damage to the

human-animal bond and relinquishment or euthanasia.

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 11 frontiersin.org

5 Limitations

This study indicates a number of areas that owners may

experience discrepancies in expectations versus experience

regarding dog ownership, however this study’s findings are subject

to several limitations. Firstly, a lack of information regarding

respondents’ expectations before acquisition precludes us from

making direct comparisons between pre- and post-acquisition

expectations and experiences. For example, wedo not know how

cautious or optimistic they were. Our data also did not capture

respondents’ previous dog ownership experience, with previous

dog experience shown to be an influential factor on owner

expectations (16); this limits the conclusions drawn from the data

somewhat. Secondly, our data are cross-sectional, and weexpect

that respondents would have owned their dogs for varying lengths

of time. The length of time the dog had been owned could have

affected respondents’ perceptions and may also introduce recall

bias relying on respondents to recall information from a long time

ago. For instance, previous research has found that dog adopters’

expectations for ownership relative to their experience changes

over time: owning a dog was considered easier than they had

expected by an increasing proportion of adopters over time (10).

Finally, the population of dogs within this study could

beconsidered “successful” relationships, given they are still living

with their owner, suggesting that many owners whose experience

violates their expectations may simply manage this. However due

to limited questions in our survey regarding welfare, we are

unable to comment on the impacts of mismanaged expectations

on the welfare or both owner and/or dogs, nor can wepredict

subsequent outcomes from this study, such as relinquishment or

euthanasia. Further research in this area would benefit from

longitudinal study design exploring owners expectations both

pre- and post-acquisition, collecting additional information such

as that listed above within the limitations of this research to allow

for a more thorough understanding of the discrepancy between

expectations and actual lived reality. Furthermore, understanding

how expectation discrepancies and surprises of ownership have

impacted dog owners and outcomes such as relinquishment is

warranted to provide deeper insight in this area.

6 Conclusion

Dog ownership can bevery valuable to humans; therefore, it is

unsurprising that they are most commonly owned companion animal

in many countries, including the UK. Oen attention is drawn towards

the perks of ownership, and the realities and consequences therefore

may not bewidely considered by potential owners. Overall, this study

indicates that owners’ reections on dog ownership are complex and

that this type of human-animal relationship involves forming close

relationships oen at a greater cost (e.g., nancial and time) than

anticipated. is study highlights that particular aspects of dog

ownership, such as the strength of bonds and the extent of the benets

and challenges, may also bedicult to fully comprehend prior to

ownership. Successful relationships, where owners are satised with

their dogs, may rely on preconceived expectations being met and

therefore our ndings suggest a need to instill realistic expectations of

dogs, and dog ownership, in aspirant owners to optimise dog and

human health and welfare.

Data availability statement

e datasets presented in this article are not readily available

because the data are not publicly available due to consent not

collected from participants to share the raw data. Requests to

access the datasets should be directed to research@

dogstrust.org.uk.

Ethics statement

e studies involving humans were approved by Dogs Trust

Ethical Review Board. e studies were conducted in accordance with

the local legislation and institutional requirements. e participants

provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis,

Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization,

Writing – original dra, Writing – review & editing. KH:

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology,

Writing – original dra, Writing – review & editing. RAC:

Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review &

editing. BC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review &

editing. RMC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis,

Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

e author(s) declare that no nancial support was received for

the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. is work

was supported by Dogs Trust and the authors are salaried employees

of Dogs Trust.

Acknowledgments

e authors would like to thank the Dogs Trust Marketing,

Communications and Digital teams for supporting the development

of the research and all dog owners who responded to the survey in this

study. Weare also grateful to Dr. Melissa Upjohn, Dr. Lauren Samet

and Dr. Sara Owczarczak-Garstecka for comments on an earlier dra

of this paper.

Conflict of interest

e authors declare that the research was conducted in the

absence of any commercial or nancial relationships that could

beconstrued as a potential conict of interest.

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 12 frontiersin.org

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent those of their aliated

organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the

reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim

that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed

by the publisher.

References

1. PDSA. PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) Report [Internet]. (2021) (Accessed

October 25, 2021). Available at: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/what-we-do/pdsa-animal-

wellbeing-report/paw-report-2021

2. Neidhart L, Boyd R. Companion animal adoption study. J Appl Anim Welf Sci.

(2002) 5:175–92. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0503_02

3. Clark CC, Gruydd-Jones T, Murray JK. Number of cats and dogs in UK welfare

organisations. Vet Rec. (2012) 170:493–3. doi: 10.1136/vr.100524

4. Lambert K, Coe J, Niel L, Dewey C, Sargeant JM. A systematic review and meta-

analysis of the proportion of dogs surrendered for dog-related and owner-related

reasons. Prev Vet Med. (2015) 118:148–60. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.

11.002

5. Coe JB, Young I, Lambert K, Dysart L, Nogueira Borden L, Rajić A. A scoping

review of published research on the relinquishment of companion animals. J Appl Anim

Welf Sci. (2014) 17:253–73. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2014.899910

6. New JC, Salman MD, King M, Scarlett JM, Kass PH, Hutchison JM. Characteristics

of shelter-relinquished animals and their owners compared with animals and their

owners in U.S. pet-owning households. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. (2000) 3:179–201. doi:

10.1207/S15327604JAWS0303_1

7. Powell L, Reinhard C, Satriale D, Morris M, Serpell J, Watson B. Characterizing

unsuccessful animal adoptions: age and breed predict the likelihood of return, reasons

for return and post-return outcomes. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:8018. doi: 10.1038/

s41598-021-87649-2

8. Hawes SM, Kerrigan JM, Hupe T, Morris KN. Factors informing the return of

adopted dogs and cats to an animal shelter. Animals. (2020) 10:1573. doi: 10.3390/

ani10091573

9. Diesel G, Pfeier DU, Brodbelt D. Factors aecting the success of rehoming dogs

in the UK during 2005. Prev Vet Med. (2008) 84:228–41. doi: 10.1016/j.

prevetmed.2007.12.004

10. Powell L, Lee B, Reinhard CL, Morris M, Satriale D, Serpell J, et al. Returning a

shelter dog: the role of owner expectations and dog behavior. Animals. (2022) 12:1053.

doi: 10.3390/ani12091053

11. Miller DD, Staats SR, Partlo C, Rada K. Factors associated with the decision to

surrender a pet to an animal shelter. J AmVet Ass. (1996) 209:738–42. doi: 10.2460/

javma.1996.209.04.738

12. Burnett E, Brand CL, O’Neill DG, Pegram CL, Belshaw Z, Stevens KB, et al. How

much is that doodle in the window? Exploring motivations and behaviours of UK

owners acquiring designer crossbreed dogs (2019-2020). Canine Med Genet. (2022) 9:8.

doi: 10.1186/s40575-022-00120-x

13. Hladky-Krage B, Homan CL. Expectations versus reality of designer dog

ownership in the UnitedStates. Animals. (2022) 12:3247. doi: 10.3390/ani12233247

14. Watson E, Niestat L. Osseous lesions in the distal extremities of dogs with

strangulating hair mats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. (2021) 62:37–43. doi: 10.1111/vru.12924

15. Powell L, Chia D, McGreevy P, Podberscek AL, Edwards KM, Neilly B, et al.

Expectations for dog ownership: perceived physical, mental and psychosocial health

consequences among prospective adopters. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0200276. doi: 10.1371/

journal.pone.0200276

16. Bouma EMC, Vink LM, Dijkstra A. Expectations versus reality: long-term research

on the dog–owner relationship. Animals. (2020) 10:772. doi: 10.3390/ani10050772

17. O’Connor R, Coe JB, Niel L, Jones-Bitton A. Eect of adopters’ lifestyles and

animal-care knowledge on their expectations prior to companion-animal guardianship.

J Appl Anim Welf Sci. (2016) 19:157–70. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2015.

1125295

18. Carroll GA, Torjussen A, Reeve C. Companion animal adoption and

relinquishment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Peri-pandemic pets at greatest risk of

relinquishment. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.1017954

19. Anderson KL, Casey RA, Cooper B, Upjohn MM, Christley RM. National dog

survey: describing UK dog and ownership demographics. Animals. (2023) 13:1072. doi:

10.3390/ani13061072

20. Creswell J, Plano-Clark V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. ird

ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Inc (2017).

21. R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing [internet].

(Accessed September 12, 2022). Available at: https://www.r-project.org

22. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006)

3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

23. Braun V, Clarke V. Reecting on reexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc

Health. (2019) 11:589–97. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

24. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview

studies. Qual Health Res. (2016) 26:1753–60. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444

25. Coe JB, Adams CL, Bonnett BN. A focus group study of veterinarians’ and pet

owners’ perceptions of the monetary aspects of veterinary care. J AmVet Med Ass. (2007)

231:1510–8. doi: 10.2460/javma.231.10.1510

26. Kedrowicz AA, Royal KD. A comparison of public perceptions of physicians

and veterinarians in the United States. Vet Sci. (2020) 7:50. doi: 10.3390/

vetsci7020050

27. Packer RMA, O’Neill DG, Fletcher F, Farnworth MJ. Great expectations,

inconvenient truths, and the paradoxes of the dog-owner relationship for owners of

brachycephalic dogs. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0219918. doi: 10.1371/journal.

pone.0219918

28. Dolan E, Scotto J, Slater M, Weiss E. Risk factors for dog relinquishment to a Los

Angeles municipal animal shelter. Animals. (2015) 5:1311–28. doi: 10.3390/ani5040413

29. Eagan BH, Gordon E, Protopopova A. Reasons for guardian-relinquishment of

dogs to shelters: animal and regional predictors in British Columbia, Canada. Front Vet

Sci. (2022) 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.857634

30. Salman MD, New JG Jr, Scarlett JM, Kass PH, Ruch-Gallie R, Hetts S. Human and

animal factors related to relinquishment of dogs and cats in 12 selected animal shelters

in the United States. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. (1998) 1:207–26. doi: 10.1207/

s15327604jaws0103_2

31. Barcelos AM, Kargas N, Maltby J, Hall S, Mills DS. A framework for understanding

how activities associated with dog ownership relate to human well-being. Sci Rep. (2020)

10:11363. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68446-9

32. Diesel G, Smith H, Pfeier DU. Factors aecting time to adoption of dogs re-

homed by a charity in the UK. Anim Welf. (2007) 16:353–60. doi: 10.1017/

S0962728600027160

33. Jensen JBH, Sandøe P, Nielsen SS. Owner-related reasons matter more than

behavioural problems—a study of why owners relinquished dogs and cats to a Danish

animal shelter from 1996 to 2017. Animals. (2020) 10:1064. doi: 10.3390/ani10061064

34. Scarlett JM, Salman MD, New JG Jr, Kass PH. Reasons for relinquishment of

companion animals in U.S. animal shelters: selected health and personal issues. J Appl

Anim Welf Sci. (1999) 2:41–57. doi: 10.1207/s15327604jaws0201_4

35. King T, Marston LC, Bennett PC. Describing the ideal Australian companion dog.

Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2009) 120:84. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2009.04.011

36. Holland KE, Mead R, Casey RA, Upjohn MM, Christley RM. Why do people want

dogs? A mixed-methods study of motivations for dog acquisition in the UnitedKingdom.

Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.877950

37. Packer RMA, Brand CL, Belshaw Z, Pegram CL, Stevens KB, O’Neill DG.

Pandemic puppies: characterising motivations and behaviours of UK owners who

purchased puppies during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Animals. (2021) 11:2500. doi:

10.3390/ani11092500

38. Morrill K, Hekman J, Li X, McClure J, Logan B, Goodman L, et al. Ancestry-

inclusive dog genomics challenges popular breed stereotypes. Science. (2022)

376:eabk0639. doi: 10.1126/science.abk0639

39. Hammond A, Rowland T, Mills DS, Pilot M. Comparison of behavioural

tendencies between “dangerous dogs” and other domestic dog breeds – evolutionary

context and practical implications. Evol Appl. (2022) 15:1806–19. doi: 10.1111/eva.

13479

40. Jagoe A, Serpell J. Owner characteristics and interactions and the prevalence of

canine behaviour problems. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (1996) 47:31–42. doi:

10.1016/0168-1591(95)01008-4

41. Kobelt AJ, Hemsworth PH, Barnett JL, Coleman GJ. A survey of dog ownership in

suburban Australia—conditions and behaviour problems. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2003)

82:137–48. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00062-5

42. Endenburg N, Bouw J. Motives for acquiring companion animals. J Econ Psychol.

(1994) 15:191–206. doi: 10.1016/0167-4870(94)90037-X

43. Franklin A. Human-nonhuman animal relationships in Australia: an overview of

results from the rst national survey and follow-up case studies 2000-2004. Soc Anim.

(2007) 15:7–27. doi: 10.1163/156853007X169315

44. Franklin A. ‘Be[a]ware of the dog’: a post-humanist approach to housing. Hous

eory Soc. (2006) 23:137–56. doi: 10.1080/14036090600813760

Anderson et al. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1331793

Frontiers in Veterinary Science 13 frontiersin.org

45. Power E. Furry families: making a human-dog family through home. Soc Cult

Geogr. (2008) 9:535–55. doi: 10.1080/14649360802217790

46. Fox R. Animal behaviours, post-human lives: everyday negotiations of the animal-

human divide in pet-keeping. Soc Cult Geogr. (2006) 7:525–37. doi:

10.1080/14649360600825679

47. Charles N. ‘Animals just love youas youare’: experiencing kinship across the

species barrier. Sociology. (2014) 48:715–30. doi: 10.1177/0038038513515353

48. Charles N, Davies CA. My family and other animals: pets as kin. Sociol Res Online.

(2008) 13:13–26. doi: 10.5153/sro.1798

49. Laurent-Simpson A. Just like family: how companion animals joined the household.

New York: NYU press (2021).

50. omas K. Man and the natural world. London: Penguin (1984).

51. Merkouri A, Graham TM, O’Haire ME, Purewal R, Westgarth C. Dogs and the

good life: a cross-sectional study of the association between the dog–owner relationship

and owner mental wellbeing. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903647

52. Ratschen E, Shoesmith E, Shahab L, Silva K, Kale D, Toner P, et al. Human-animal

relationships and interactions during the Covid-19 lockdown phase in the UK:

investigating links with mental health and loneliness. Triberti S, editor. PLoS one. (2020)

15:e0239397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239397

53. Applebaum JW, Tomlinson CA, Matijczak A, McDonald SE, Zsembik BA. e

concerns, diculties, and stressors of caring for pets during COVID-19: results from a

large survey of U.S. pet owners. Animals. (2020) 10:1882. doi: 10.3390/ani10101882

54. Holland KE, Owczarczak-Garstecka SC, Anderson KL, Casey RA, Christley RM,

Harris L, et al. “More attention than usual”: a thematic analysis of dog ownership

experiences in the UK during the rst COVID-19 lockdown. Animals. (2021) 11:240.

doi: 10.3390/ani11010240

55. Archer J, Winchester G. Bereavement following death of a pet. Br J Psychol. (1994)

85:259–71. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1994.tb02522.x

56. Field N, Orsini L, Gavish R, Packman W. Role of attachment in response to pet

loss. Death Stud. (2009) 33:334–55. doi: 10.1080/07481180802705783

57. Wrobel TA, Dye AL. Grieving pet death: normative, gender, and attachment issues.

OMEGA J Death Dying. (2003) 47:385–93. doi: 10.2190/QYV5-LLJ1-T043-U0F9

58. Eckerd LM, Barnett JE, Jett-Dias L. Grief following pet and human loss: closeness

is key. Death Stud. (2016) 40:275–82. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2016.1139014

59. Mead R, Holland KE, Casey RA, Upjohn MM, Christley RM. “Do your homework

as your heart takes over when yougo looking”: factors associated with pre-acquisition

information-seeking among prospective UK dog owners. Animals. (2023) 13:1015. doi:

10.3390/ani13061015